On April 2, 2025, the Trump administration announced a new tariff policy to reshape trade between the United States and the rest of the world, including Africa. The policy introduced a baseline 10% tariff on all goods entering the U.S., with higher rates reaching up to 50% for countries running significant trade surpluses with the U.S. This will impact earlier trade arrangements like the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and disadvantage several African economies.

At the center of this policy is a formula that sets country-specific tariff rates based on trade imbalances. The Trump reciprocal tariff formula is straightforward in theory:

Tariff rate = max (10%, Trade Deficit ÷ Imports × 0.5)

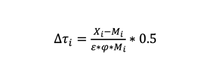

However, to give it more technical weight, the U.S. Trade Representative introduced a formal version of the same concept, expressed as:

- Xᵢ is U.S. exports to country i

- Mᵢ is U.S. imports from country i

- ε is the elasticity of U.S. import demand (set at -4)

- φ is the tariff pass-through to prices (set at 0.25).

This formula ties tariffs to the degree of trade imbalance, adjusted for economic responsiveness. Whether framed in policy terms or laid out through economic equations, the outcome is the same: countries running large trade surpluses with the U.S. face higher tariffs. The logic may appear technical, but its meaning is simple; the more a country sells to the U.S. without buying in return, the steeper the tariff it will face.

For many African countries, this shift will impact export revenues. Higher tariffs will make African goods more expensive in U.S. markets, reducing demand and revenue. Lesotho is a clear example. In 2024, it exported $237.3 million of textiles to the U.S. Under a 50% tariff and assuming a demand elasticity of -1.5, exports could decline by as much as 75%, slashing export revenue to $59.3 million. This would have devastating impacts on an economy where textile factories employ thousands. Lesotho is not alone. South Africa, with $14.7 billion in exports to the U.S., faces a 30% tariff. If exports fall by 30%, the loss will total $4.41 billion. Using an export multiplier of 1.5 could reduce South Africa’s GDP by up to $6.61 billion, particularly in sectors like mining and manufacturing, which rely heavily on U.S. demand.

Angola, one of Africa’s top oil exporters, now faces a 32% tariff. While oil is a globally traded commodity, a slight buyer preference or pricing shift can significantly affect national revenues. A 15% drop in U.S. oil purchases could translate into billions in lost earnings for Angola, putting pressure on foreign exchange reserves and public finances. Angola is not the only country vulnerable to changes in a single export market. Madagascar, facing a 47% tariff, is similarly in a difficult position. Its textile sector, heavily focused on the U.S. market, could experience sharp export declines, leading to job losses in export-processing zones.

Africa’s increasing reliance on China further increases vulnerability. This dependence extends beyond China being a buyer of raw materials; it also includes reliance on imported goods and industrial machinery. If inflation rises in China, it will consequently increase the cost of finished goods shipped to Africa. For countries like Nigeria, already contending with a 14% U.S. tariff and reliant on Chinese imports, this means rising costs on both ends – more expensive imports and shrinking export revenues. And the risk doesn’t stop with inflation. If China slows down its imports due to its internal economic strain, African countries could have a double hit: first by reduced access to the U.S. market due to tariffs, and then by falling demand from China. Lesotho’s textiles and Angola’s oil are both exposed in this scenario. As demand shrinks, currencies could weaken, and the cost of imported goods could surge, deepening economic strain across the continent.

The broader picture is just as troubling. Africa exported $39.5 billion to the U.S. in 2024. A 10 – 20% decline triggered by these tariffs would strip away $3.95 to $7.9 billion in export revenue. That’s enough to shave between 0.2% and 0.4% off Africa’s GDP growth. For economies still recovering from the effects of COVID-19, inflation, and rising debt levels, this additional pressure could stall recovery and slow structural progress.

Trump’s tariff regime signals a more profound shift from cooperation to confrontation. For African countries, the lesson is clear: relying too heavily on one market is no longer a safe strategy. Moving forward, African countries must strengthen regional value chains, expand intra-African trade, and boost their export competitiveness in markets beyond the U.S.

References

Africa | United States Trade Representative. (2025). Ustr.gov. https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/africa